He leaves behind a body of work so sprawling—shorts, documentaries, features, TV movies, series—that his CV alone might be longer than an obituary

Shyam Benegal

Shyam Benegal’s last work, Mujib (2023), was possibly the most important film for Bangladesh; a biopic on the neigbouring nation’s founder, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He was 89, when the movie released. You did well, Mr Benegal. His first feature, Ankur (1974), was possibly the most important Hindi film for India’s art-house movement, heralding the Indian New Wave, from Bombay.ADVERTISEMENTIn between is a life so full of all kinds of cinema—shorts, documentaries, features, TV movies, series—that his CV alone, let alone its range, might be longer than an obituary can do justice. This would include a series of firsts; again, starting with Ankur itself, that was actor Shabana Azmi’s screen debut. Nishant (1975) was Naseeruddin Shah’s. He picked both actors, after they’d graduated from Pune’s Film & Television Institute of India.Shyam Benegal. Pic/AFPOne evening, while watching news on television, the anchor caught his eye, and he cast her in his children’s film, Charandas Chor (1975). That was Smita Patil. Bhumika remains, arguably, her greatest performance. Between Naseer, Shabana and Smita, forming an alternate, Bombay star-system of their own—besides Om Puri (Susman, Arohan), Anant Nag (Konduran, Kalyug), Rajit Kapur (The Making of the Mahatma, Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda), and so many others—Benegal didn’t just make films.

He built an entire eco-system, for what came to be known as Hindi parallel cinema. Named such, because it did not intersect with the Bombay mainstream—remaining true to its realism, social consciousness, barely appeasing to audience’s baser instincts, or ignoring its intellect, while staying within commercial cinema, after all, for his features were still mostly privately funded (Blaze Productions, in particular).

An unassuming, gentle soul, gifted with gravitas, foremost, Benegal was a young mind. How else do you explain a career scripted over seven decades. Consider that when he made his first short, in 1962 (Ghar Betha Ganga), Jawaharlal Nehru was still India’s Prime Minister; man was several years away from stepping on the moon; and it’d be 20 years before we’d get Doordarshan (DD) for a proper national broadcaster.

Last checked, Benegal was still making movies. His partner, Nira, both in life and films, was his sounding board. He gave DD, and indeed Indian television, its greatest OTT slow-burn, decades before there was OTT, with Bharat Ek Khoj (1988), based on Nehru’s Discovery of India. He made India’s crowd-funded film, Manthan (1976), based on the life of dairy engineer, Verghese Kurien, with contribution of 500,000 farmers, decades before crowd funding became a term.

With Junoon (1979), he made the sharpest effort, until then, to take art-house into a big-budget space, with stalwarts of the time, adapting Ruskin Bond’s A Flight of Pigeons. At the turn of the century, when multiplexes offered a short-lived window into exploring meaningful yet entertaining content, beyond simply the starry space, he brought forward intelligent comedies, Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008), Well Done Abba! (2009).

This is before he swiftly switched gear, and embarked on the astoundingly ambitious series, on the making of the Indian Constitution, Samvidhaan (2014), for Rajya Sabha TV. Yup, Benegal has always been there. Not just in terms of works, but also for how he inspired. What’s the final shot in Nagraj Manjule’s Fandry (2013), if not the stone-throwing finale of Ankur!

Given the widest possible gamut, surely, everybody has a Benegal Top 10. And each might read so different from the other. Kalyug (1981), modern adaptation of Mahabharat, set in Bombay’s corporate world, tops mine; Mammo (1994) might be a second; Mandi (1983) could be yours, or Zubeidaa (2001), if you’re younger.

A cousin of Guru Dutt, who got interested in cinema, because of his photographer-father Sridhar Benegal, who gave him access to a movie camera, when he was only 12—once Benegal moved to Bombay, from Hyderabad, he started out as a man of advertising.

It’s something he shared with Satyajit Ray, his inspiration of sorts. One of the most enlightening conversations on cinema that Benegal left behind for film buffs was his interview with Ray himself, for a documentary (that occasionally appears and disappears from YouTube).

It’s where you see Benegal for simply a curious movie mind. And a consummate movie buff, you would always spot at screenings at cinemas and festivals. The last I met him, in 2019, at his Tardeo office, which is a shrine of sorts in filmmakers in Mumbai—it was right after his Manthan actor and long-time associate, Girish Karnad, had passed on.

“Everybody’s leaving now,” he said. The very next minute, he began revealing how the then Bangladesh PM, Sheikh Haseena, had entrusted him with a film on her father, Mujib, along the lines of Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi. Benegal was 85 then—speaking about recommendations to the Indian censor board that never got implemented, or his public commitments in Goa, initiated from his Member of Parliament fund.

We discussed movies as a changing medium. He told me the cellphone was the best way to watch films—the eye’s distance should, anyway, be one and half times the length of the screen’s diagonal, and the sound doesn’t get better than a headphone. I’ve followed his advice since. There was so much more to learn. The movies remain. He lives on forever.

Shyam Benegal’s last work, Mujib (2023), was possibly the most important film for Bangladesh; a biopic on the neigbouring nation’s founder, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He was 89, when the movie released. You did well, Mr Benegal. His first feature, Ankur (1974), was possibly the most important Hindi film for India’s art-house movement, heralding the Indian New Wave, from Bombay.

ADVERTISEMENT

In between is a life so full of all kinds of cinema—shorts, documentaries, features, TV movies, series—that his CV alone, let alone its range, might be longer than an obituary can do justice. This would include a series of firsts; again, starting with Ankur itself, that was actor Shabana Azmi’s screen debut. Nishant (1975) was Naseeruddin Shah’s. He picked both actors, after they’d graduated from Pune’s Film & Television Institute of India.

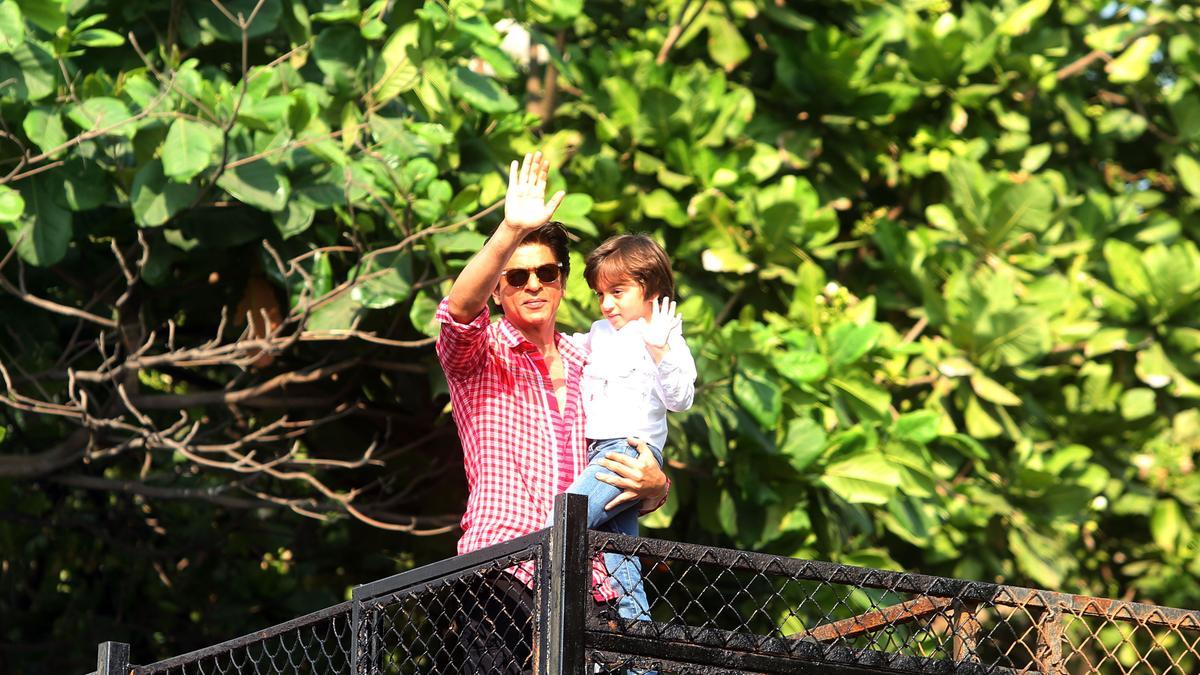

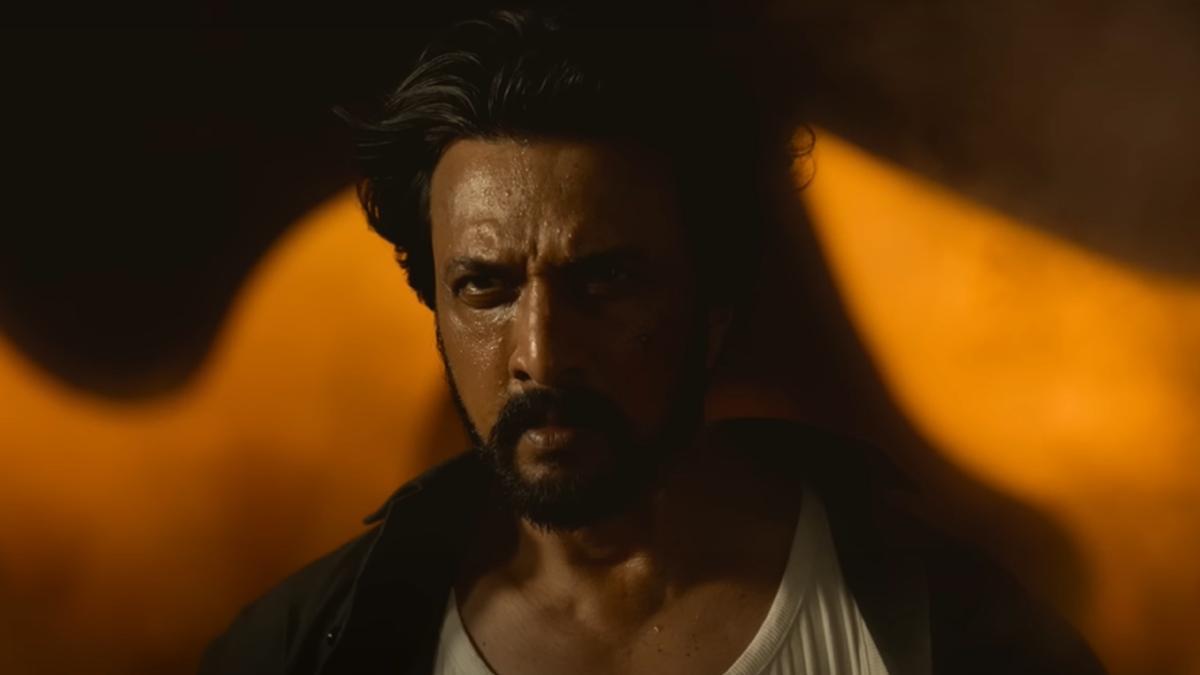

Shyam Benegal. Pic/AFP

One evening, while watching news on television, the anchor caught his eye, and he cast her in his children’s film, Charandas Chor (1975). That was Smita Patil. Bhumika remains, arguably, her greatest performance. Between Naseer, Shabana and Smita, forming an alternate, Bombay star-system of their own—besides Om Puri (Susman, Arohan), Anant Nag (Konduran, Kalyug), Rajit Kapur (The Making of the Mahatma, Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda), and so many others—Benegal didn’t just make films.

He built an entire eco-system, for what came to be known as Hindi parallel cinema. Named such, because it did not intersect with the Bombay mainstream—remaining true to its realism, social consciousness, barely appeasing to audience’s baser instincts, or ignoring its intellect, while staying within commercial cinema, after all, for his features were still mostly privately funded (Blaze Productions, in particular).

An unassuming, gentle soul, gifted with gravitas, foremost, Benegal was a young mind. How else do you explain a career scripted over seven decades. Consider that when he made his first short, in 1962 (Ghar Betha Ganga), Jawaharlal Nehru was still India’s Prime Minister; man was several years away from stepping on the moon; and it’d be 20 years before we’d get Doordarshan (DD) for a proper national broadcaster.

Last checked, Benegal was still making movies. His partner, Nira, both in life and films, was his sounding board. He gave DD, and indeed Indian television, its greatest OTT slow-burn, decades before there was OTT, with Bharat Ek Khoj (1988), based on Nehru’s Discovery of India. He made India’s crowd-funded film, Manthan (1976), based on the life of dairy engineer, Verghese Kurien, with contribution of 500,000 farmers, decades before crowd funding became a term.

With Junoon (1979), he made the sharpest effort, until then, to take art-house into a big-budget space, with stalwarts of the time, adapting Ruskin Bond’s A Flight of Pigeons. At the turn of the century, when multiplexes offered a short-lived window into exploring meaningful yet entertaining content, beyond simply the starry space, he brought forward intelligent comedies, Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008), Well Done Abba! (2009).

This is before he swiftly switched gear, and embarked on the astoundingly ambitious series, on the making of the Indian Constitution, Samvidhaan (2014), for Rajya Sabha TV. Yup, Benegal has always been there. Not just in terms of works, but also for how he inspired. What’s the final shot in Nagraj Manjule’s Fandry (2013), if not the stone-throwing finale of Ankur!

Given the widest possible gamut, surely, everybody has a Benegal Top 10. And each might read so different from the other. Kalyug (1981), modern adaptation of Mahabharat, set in Bombay’s corporate world, tops mine; Mammo (1994) might be a second; Mandi (1983) could be yours, or Zubeidaa (2001), if you’re younger.

A cousin of Guru Dutt, who got interested in cinema, because of his photographer-father Sridhar Benegal, who gave him access to a movie camera, when he was only 12—once Benegal moved to Bombay, from Hyderabad, he started out as a man of advertising.

It’s something he shared with Satyajit Ray, his inspiration of sorts. One of the most enlightening conversations on cinema that Benegal left behind for film buffs was his interview with Ray himself, for a documentary (that occasionally appears and disappears from YouTube).

It’s where you see Benegal for simply a curious movie mind. And a consummate movie buff, you would always spot at screenings at cinemas and festivals. The last I met him, in 2019, at his Tardeo office, which is a shrine of sorts in filmmakers in Mumbai—it was right after his Manthan actor and long-time associate, Girish Karnad, had passed on.

“Everybody’s leaving now,” he said. The very next minute, he began revealing how the then Bangladesh PM, Sheikh Haseena, had entrusted him with a film on her father, Mujib, along the lines of Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi. Benegal was 85 then—speaking about recommendations to the Indian censor board that never got implemented, or his public commitments in Goa, initiated from his Member of Parliament fund.

We discussed movies as a changing medium. He told me the cellphone was the best way to watch films—the eye’s distance should, anyway, be one and half times the length of the screen’s diagonal, and the sound doesn’t get better than a headphone. I’ve followed his advice since. There was so much more to learn. The movies remain. He lives on forever.