In the realm of artistic legendary figures, there are those who create for the sheer love of it, often detached from the overwhelming recognition their work might garner. This holds true for the 87-year-old Gujarat-based maestro, Gulam Mohammed Sheikh. Known not just for his captivating paintings, but also for his compelling prose, the acclaimed artist has a fascinating yet lesser-known penchant for printmaking. Now, Bengaluru is hosting an exhibition that shines the spotlight on Sheikh’s extensive body of work in prints, a retrospective entitled “Handprints.” Curated by Pushpamala N, the exhibit showcases 60 prints that span an impressive seven decades, dating back to Sheikh’s student days in 1965 up to the present.

The genesis of this enlightening showcase was somewhat serendipitous. A casual conversation between Pushpamala and Sheikh about exhibiting his paintings revealed that his rich collection of prints had never been shown in a solo exhibition before. “I’ve known him since 1977, and even as his student, I wasn’t fully aware of the extensive body of work in prints until this dialogue began,” says Pushpamala.

Printmaking is a versatile realm, involving styles like woodcut, linocut, etching, aquatint, and lithography, as well as modern techniques such as screen and digital printing. Handprints focuses on Sheikh’s traditionally executed prints, necessitating a two-part exhibition due to the sheer volume of his work. Part one features these conventional print techniques.

“Gulam is a multifaceted talent—a celebrated artist, poet, writer, art historian, and influential teacher. All these elements are intricately woven into his prints,” Pushpamala notes. His journey in art and literature has been simultaneous. He began penning memoirs in the late ’60s, which got published four decades later, reflecting the literary and historical resonance in his artwork.

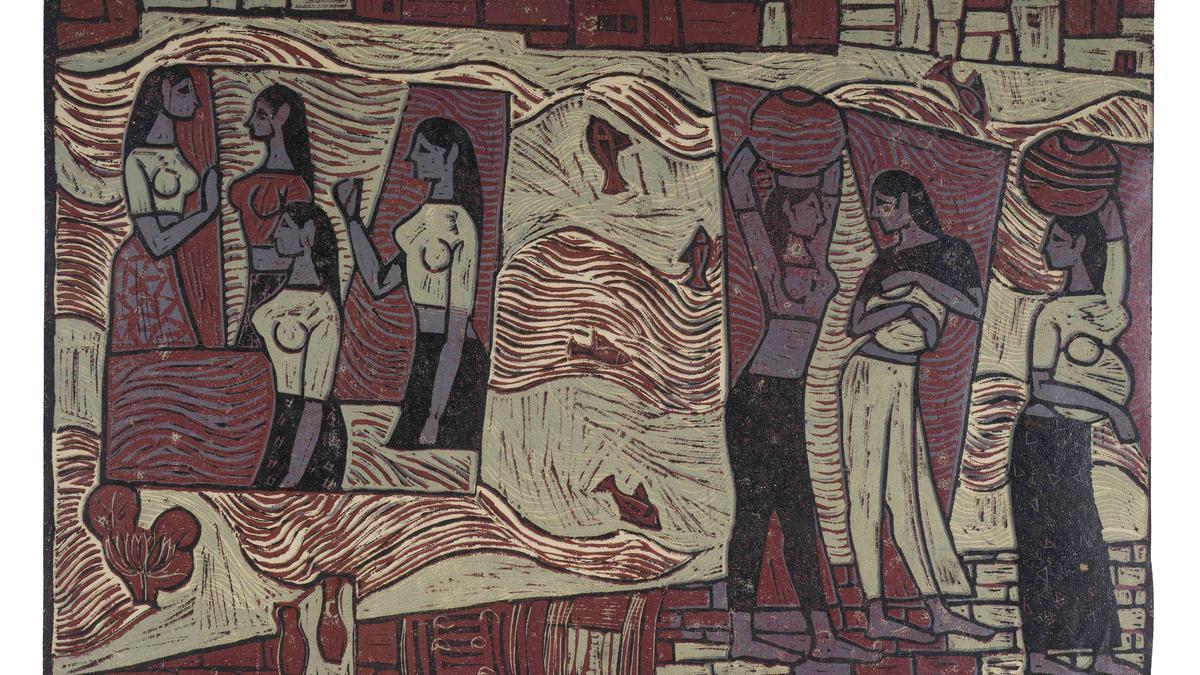

One of the standout pieces in the exhibition, “The Riot,” reflects on the violent communal riots in Baroda during 1968-69. Sheikh, once identifying with a Nehruvian secularist vision of a free and open world, found himself confronted with the harsh reality of being perceived as ‘The Other.

.’ However, his work does not merely capture a personal ordeal; it also pays homage to the 16th-century Mughal folio, Hamzanama, blending historical art with contemporary experiences.

Pushpamala meticulously curated the exhibit chronologically to amplify the narrative of Sheikh’s life and concurrent historical events. “It serves as a pedagogical tool for students and visitors, showcasing Gulam’s enthusiasm and experimental approach with different media and techniques,” she elaborates.

The exhibition does more than just display Sheikh’s proficiency in printmaking with its array of woodcut, linocut, etching-aquatint, lithography, and silkscreen works. It also delves into his childhood artistry, featuring handwritten magazines, comic strips, and illustrations created while he was still in school. “These elements will resonate deeply with today’s young artists who are engaged in creating zines,” believes Pushpamala.

By the tender age of 15, Sheikh was illustrating for his school’s literary magazine, Pragati, later contributing to the avant-garde magazine Kshitij during his art student days. His expertise in printmaking allowed him to enhance the magazine with lino cuts and other illustrations. His collaborative effort in launching the magazine Vrishchik with Bhupen Khakhar marks another milestone where linocuts and lithographs served both as content and covers, pushing the boundaries of art into the literary and public domains.

Handprints sets the stage for Mindprints, the second part of this retrospective, which will be on exhibit from August 17. While the former is monochromatic, a reflection of traditional printmaking techniques, Mindprints will introduce more contemporary and colorful digital prints. Pushpamala reveals that Sheikh was among the pioneers of digital printing in India, beginning in the late ’90s and early 2000s—a time when the art form was met with skepticism.

Mindprints promises to explore Sheikh’s infatuation with pre-Renaissance art from Western cultures, Persia, Turkey, and China, entwining autobiographical references and perspectives on urban landscapes and maps. His cityscapes, imbued with a sense of magic realism and miniature art, are noted for their non-realistic, even distorted imagery. “His maps sometimes open like books, adorned with snakes and ladders or surrounding city outlines, offering a magical yet historical perspective,” says Pushpamala.

The retrospective also includes a compelling 45-minute video of Sheikh in conversation with artist Vasudevan Akittham, adding depth to the exhibit. Handprints, for those captivated by the intersections of history, culture, and personal narrative in art, is on display at Gallery Sumukha until July 27.