In the intricate world of filmmaking, countless hours of footage are meticulously reviewed, edited, and stitched into a compelling narrative that ultimately graces the silver screen. Despite being integral to the creative process, the editors who shape these stories often remain unseen, both literally and figuratively. Recently, Bollywood’s leading editors have come forward to protest against the unjust working conditions they face, highlighting a fundamental issue: unfair meal reimbursements.

Last November, a report from mid-day shed light on efforts by a group of editors to seek fair working conditions, engaging with the Association of Film and Video Editors (AFVE) and the Federation of Western India Cine Employees (FWICE). Almost a year later, their struggles seem to have intensified, with production houses continuing discriminatory practices, this time focusing on the provision–or lack thereof–of basic meal allowances.

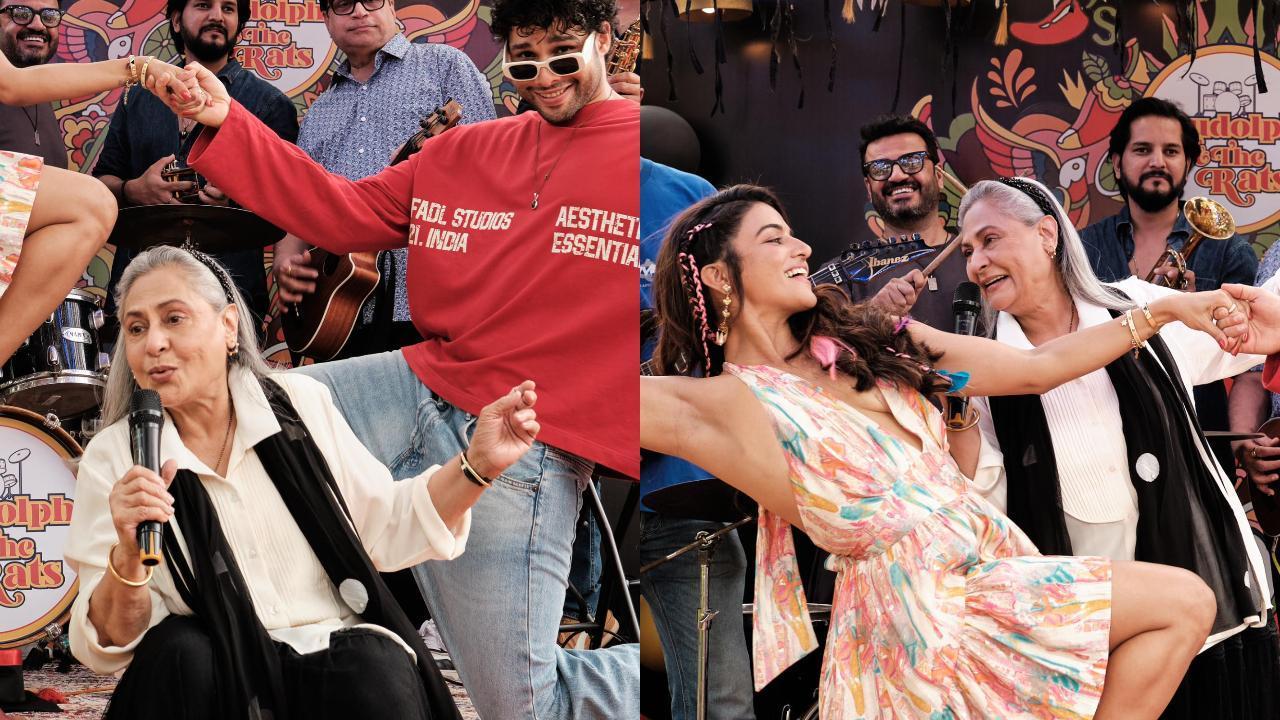

Noteworthy collaborations on the horizon include projects by editors Shweta Venkat and Antara Lahiri. Venkat is working on Junaid Khan’s “Maharaj,” while Lahiri is editing Ananya Panday’s “Call Me Bae.” Lahiri recently revealed that it was only until recently that many editing teams were neither provided with meals nor reimbursed for their food expenses. “It’s disheartening, but meal expenses now need to be part of our negotiations. If you don’t bring it up, productions assume you’ll never be eating throughout the project,” she remarks with dry sarcasm.

Lahiri pointed out that the imposition of meal reimbursement caps is a concerning new development. Shockingly low food budgets are allotted to editors, in stark contrast to the lavish dining options provided for actors, filmmakers, and on-set teams. “There’s a bizarre inequity in how meal caps are imposed. A head of department like an editor can order a meal worth roughly Rs 700, but an associate or assistant editor has a cap of Rs 400-500. Why there is a hierarchy in food is beyond me!” she exclaims. Lahiri adds, “Sometimes, directors and production teams boast about the gourmet food served on set. But the same teams expect us to survive on cheap, greasy dabba. It raises eyebrows if you or your team wants to eat healthily. Is it only an actor’s prerogative to stay fit?”

But the issue of meal quality goes beyond budget. Lahiri recalls a shocking incident where the editing team was served contaminated food. “I once found worms in the rice, and this was from a tiffin service ordered by a well-known production house,” she recounts.

Veteran editor Deepa Bhatia, known for her work on “Taare Zameen Par” (2007) and “Kedarnath” (2018), notes that the responsibility for covering food costs traditionally lay with the producers, a practice that seems to be fading. Bhatia points out, “Producers now find the meal costs of assistant editors too burdensome.

. However, the costs associated with stars’ entourages are considered affordable. The inequality is alarming.”

An editor, who requested anonymity, shared the dire situation he recently faced. “On my last project, two team members had a per-day food limit of just Rs 150. With that amount, you could probably only get an omelette,” he laments. Another editor, currently working on a new series, explains that his team was given a choice: order food worth Rs 150 or have the production house provide a lunchbox. Opting for the latter turned disastrous when the entire team suffered from food poisoning within a week.

The grievances do not stop there. An insider reveals that some production houses adjust the food budget depending on the scale of the film. “The team working on high-budget spectacle projects gets better quality food than those on small-budget films,” the source discloses.

Shweta Venkat, who has worked on “Maharaj” and “Thank You For Coming,” claims that the discrimination in meal provisions is indicative of a larger issue. “Our community is grossly underpaid. While movie budgets have grown and actors and technicians command higher fees, post-production and editing teams still operate on outdated rates. If a project has a budget in crores, given the effort an assistant editor puts in, their pay must reflect this,” Venkat insists. She adds that under the current pay scales, it is nearly impossible for an assistant editor to sustain themselves in Mumbai.

As editors grapple with restrictive food budgets, low wages, and a lack of transportation allowances, the prevailing sentiment is that producers lack any real incentive to treat them with dignity. Venkat and Bhatia see a need for urgent and affirmative action to combat this discrimination. “Over the last four to five years, a number of us have come together to figure out solutions. We’ve initiated efforts with AFVE and are attempting to mobilise the community,” states Venkat. Lahiri, however, voices a concern about the hesitancy within the editor community to speak out. “There’s a pervasive fear of being blacklisted. Each time we attempt to move forward with union efforts, progress stalls because few editors are willing to file formal complaints,” she explains.

The road ahead remains challenging, with Bollywood’s editors calling for the industry to recognize and rectify their plight, ensuring that the very people who narrate the stories behind the scenes are treated with fairness and respect.