Envision a canvas that captures the essence of football – the dynamic dribbles and the adrenaline-pumping goal attempts meticulously immortalized in cinematic form. This is precisely what you’ll find in “Maidaan,” a film where the visual splendor matches the expansive reach of the big screen, perhaps justifying its availability in IMAX, albeit the full potential of that format remains uncertain.

Portrayed in lush cinematography, “Maidaan” serves up a visual feast, especially when it bears the responsibility of portraying football – a sport whose filming requires a distinctive finesse, setting it apart from its real-time, live-broadcast counterpart. The film presents reenactments of historical matches, including memorable moments from three Olympic Games and an Asian event, carefully capturing the period from the 1950s to the early ’60s.

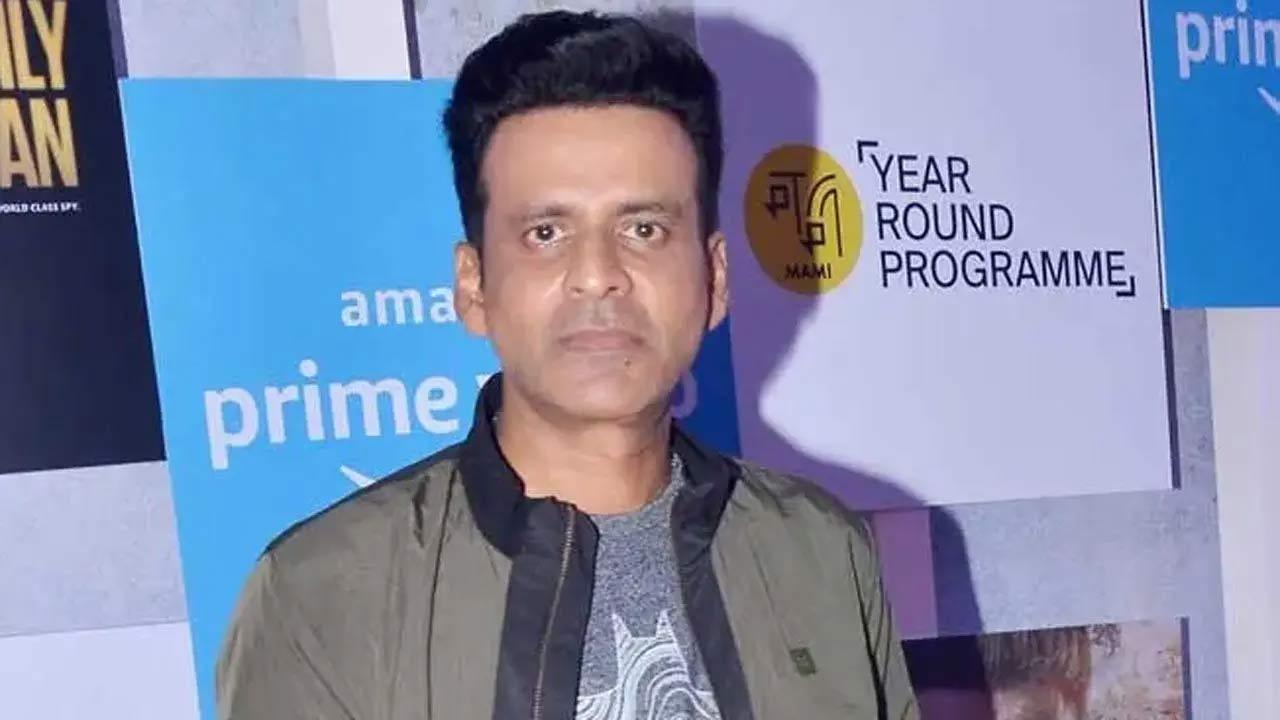

At the heart of these visuals stands Bollywood heavyweight Ajay Devgn, playing the protagonist with a subtlety that has become his trademark, yet so nuanced that it risks being underappreciated. Throughout the film, he brandishes a single prop – a cigarette – which, despite the ever-present statutory health warnings, signifies his indefatigable spirit, even as his character grapples with a severe illness.

But the film’s storyline, much like the smoke from the protagonist’s cigarette, seems to waft away, leaving little but a cautionary message about the dangers of smoking. It takes on the vibe of a prolonged public-service announcement, with the dangers of smoking vividly illustrated against the backdrop of the protagonist’s struggle.

This leads us to question who the real antagonist is. The literal embodiment of opposition is actor Gajraj Rao, who transforms remarkably into a composite character – India’s premier sports journalist cum publisher cum editor cum reporter – a man with enough clout to sway political fortunes, but who inexplicably harbors animosity towards the Indian football team’s global aspirations.

At his side is a subordinate, portrayed by Rudranil Ghosh, who presides over the football federation and together they form a duo of clichéd villains unlike any other. However, the real nemesis could very well be the harsh reality – that India has historically not been a powerhouse in the realm of world-class football. This is the underlying struggle that “Maidaan” sets out to explore, inspired by the life of Syed Abdul Rahim, the unheralded coach who once brought the Indian team close to international acclaim.

Stylistically, Devgn channels a reminiscent flair, evocative of Indian cricket legend Mohd. Azharuddin, though the film’s adherence to historical accuracy isn’t its primary aim. Instead, “Maidaan” should be judged on the story it tells, much like the acclaimed “Chak De! India” which, while rooted in reality, chose a fictionalized protagonist to elevate its narrative.

Comparisons with “Chak De! India” are inevitable, as both movies situate themselves within the sporting genre. However, “Maidaan” falters where the former excelled – in its script. “Chak De!” thrived on a focused narrative, honing in on the coach and his team. In contrast, “Maidaan” meanders through a convoluted script penned by a committee of writers – Saiwyn Quadras, Aman Rai, Atul Shahi, Ritesh Shah, Sidhant Mago, Akash Chawla, Arunava Joy Sengupta, along with director Amit Ravindernath Sharma.

This diffusion of narrative perhaps contributes to the film’s inadequacies. There’s a tantalizing glimpse into the personas of football legends PK Banerjee, Neville D’Souza, and Chuni Goswami, but the film shies away from diving deep into their stories or psyche, instead opting to sideline their legacy for protracted sub-plots and unwarranted antagonists that fail to do justice to their stature.

For a sprawling narrative exceeding three hours, there is a tipping point where the audience’s patience is tested. Amid the plot’s aimlessness and the surplus of writerly interpretations, the sensation of fatigue creeps in. “Maidaan” could do with a tighter storyline that celebrates the spirit and tribulations of Indian football without undue diversions, but as it stands, many may exit the cinematic playing field thinking, “Okay then. I’m done.”